The Risk and Rewards of Adventure Tourism

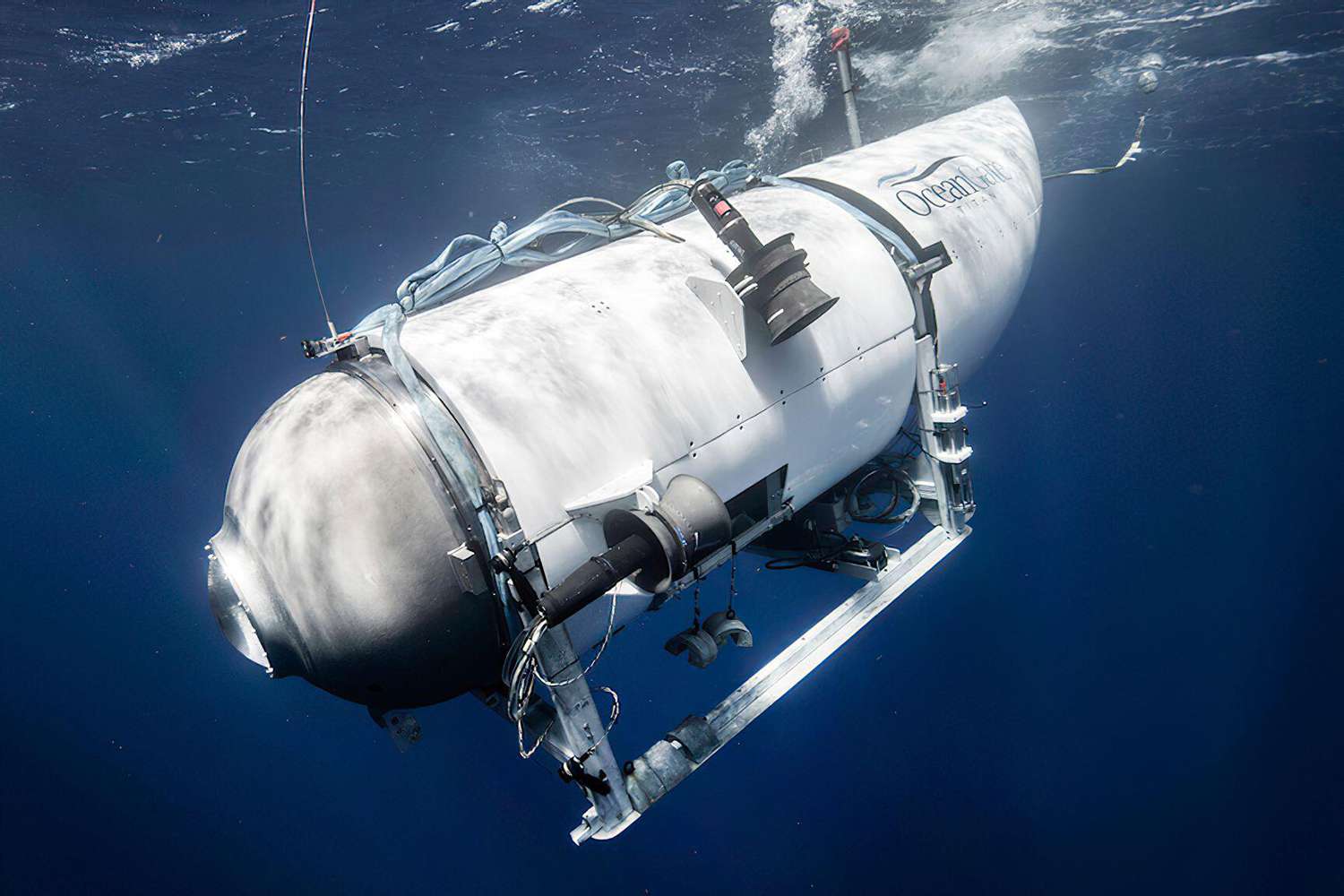

The tragic loss of life involving the five passengers aboard the OceanGate Titan submersible has sparked a crucial debate - when does adventure tourism cross the line into unacceptable risk?

“A ship is safe in harbour, but that’s not what ships are built for.” – John G. Shed

Humankind has always had an innate desire to discover and explore.

This spirit of adventure has driven us on as a species and led us to scientific, geographical and even philosophical insights that a less curious being may never have uncovered.

But, as John G. Shed's quote above alludes to, exploration often contains an element of danger. The greatest discoveries that humans have made (landing on the moon, splitting the atom etc) are often those with the greatest risk factors.

In the context of evolution and human development, we can often justify these dangers - with great risk comes great reward after all.

However, it is harder to make a logical case for taking such risks when the object of the endeavour is simply entertainment or a tourism-driven experience.

Witness the mix of reactions to the doomed OceanGate Titan submersible disaster.

While most reasonable commentators recognise that this was a tragic loss of life, there was also an anger in certain quarters that these individuals had risked their safety for what was seen as a frivolous tourism jaunt.

A defence of the OceanGate mission by its co-founder.

There is always a calculation to be made involving the dangers of an activity balanced against the anticipated value to be gained.

The issue is that people's definition of value here can vary quite significantly. Can an experience that offers no real tangible gain or outcome be justified when the stakes are so high?

It probably didn't help that most of the people aboard the vessel were multi-millionaires, to whom the sympathy of the general population is harder to evoke at the best of times.

However, the incident and the media storm that surrounded it does beg the question: how far is too far when it comes to risk and adventure tourism?

The rise of adventure tourism

The term "adventure tourism" covers quite a broad range of activities, from hiking in the mountains to blasting off into outer space.

As this Grand View Research article shows, the US adventure tourism market has shown consistent growth over recent years and is projected to see a compound annual growth rate of 14-15% between now and 2030.

With an anticipated worldwide market value of one trillion USD by the end of the decade, this is clearly a form of tourism that cannot be ignored by the industry.

From the consumer perspective, adventure tourism offers a more immersive form of travel that is experience based and promises a greater cultural insight than can be achieved by just sitting on a beach for a week.

Unsurprisingly, a key market demographic here is the younger, more affluent traveller who would prefer to identify as an "adventurer" rather than a "tourist".

For the industry, this form of tourism offers great marketing potential precisely because it appeals to how we like to view ourselves as travellers.

The very essence of the term "adventure" holds within it the promise of profound exploration, not only of the external world but also of our own inner selves.

In an age where discovery both of the 'self' and wider experiences is increasingly valued, this is a highly-desirable quality for a tourism product to possess.

No matter the actual risk factor of the activity involved, the perception here is what really matters, and this can be utilised in promotions to enhance the value proposition of the tourism experience.

It is no wonder that companies and tour agents such as MySwitzerland dedicate entire sections of their websites to adventure tourism offerings.

Lots of us would like to think of ourselves as the next Christopher Columbus or Marco Polo; however, for most of us, we would prefer our adventures to be in controlled environments where our safety is guaranteed.

Risky business

Of course, it is the element of risk - however great or small - that distinguishes adventure tourism from other forms of holiday.

It is telling that these travel experience are categorised as either soft adventure tourism - activities such as hiking or scuba diving with a lower danger element - and hard adventure tourism, e.g. bungee jumping, ice climbing or sky diving, where the risk factor increases.

Sky-diving would be an example of hard adventure tourism.

For the majority of adventure tourists, the knowledge that they are in a professionally-controlled environment is crucial to their enjoyment of the activity or experience.

Although they may not explicitly acknowledge it, there is little chance they would participate in the activity outside this context of perceived safety.

For others, there seems to be an exponential increase in the level of enjoyment as the risk factor increases.

From this perspective, a true adventure is one where an element of control has to be rescinded and the participant is, to some extent, stepping into the unknown.

Speaking of stepping into unknown, this Mountain Culture Magazine interview with BASE jumper Sean Chuma offers a good insight into the mind of those who like to live their lives slight closer to the edge.

"I want to be clear about something: it’s not about being crazy. A lot of people call us adrenaline junkies but most BASE jumpers are intelligent and think things through. It’s very calculated."

While Chuma's point is valid (especially when it comes to people who devote their lives to an activity or sport) for the adventure tourist, the adrenaline buzz clearly plays a part.

With hard adventure tourism activities becoming more widespread and accessible for those with the finances and free time to enjoy them, the barrier for entry to high-risk experiences becomes lower.

And, like most things that stimulate our bodies or minds, once you get a taste of an adrenaline kick, it can become addictive.

The challenge then becomes to recreate that feeling and this often leads people to find an experience with an even higher risk factor or danger element.

This in-and-of-itself is not necessarily a bad thing, especially if you follow the principle that we have free-will and, so long as we aren't harming others, we should be at liberty to behave as we wish.

However, it is rarely that simple. Not many people live in isolation and our actions, and the risks we choose to take, have potential for friends, family members and loved ones.

One of the saddest stories to come out of OceanGate disaster was that of the Pakistani father and son onboard - reports claimed that the son was reluctant to go on the voyage but didn't want to let his parent down on what would be Father's Day in the United States.

Those who engage in high-risk activities - even those with the skill-sets and experience of a Sean Chuma - increase their exposure to the risk of injury or death and this becomes a burden of responsibility when they have family or dependants.

The other concern is that, once the need for thrill and adventure reaches a certain level, it naturally becomes an elitist preserve - accessible only to those with the greatest of resources.

Which leads us to...

To infinity and beyond

When Elon Musk launched SpaceX in 2002, its stated aims were to reduce the cost of space transportation and colonise planet Mars.

Alongside fellow billionaires Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson, Musk is part of the next generation of "space race", aiming to make interplanetary travel and colonisation a practical and economic reality for mankind.

Jeff Bezos was part of his Blue Origin company's inaugural space flight

With ever-increasing environmental pressures on planet Earth, the ability to expand our habitable universe may well prove crucial to our long-term ability to survive and prosper.

However, the concern here is that relying too heavily on business enterprises (as opposed to elected powers or international cooperation) to provide solutions to humankind's existential angst may prove misguided.

While the mission statements of these companies seem noble, it is noticeable over recent years that the focus seems to have shifted more to providing commercial tourism opportunities to the ultra-wealthy.

Like with the failed OceanGate expedition to view the wreckage of the Titanic, the line between valuable exploration and commercial adventure becomes blurred.

Ultimately, a businesses' focus is on its bottom line and, as the technologies develops, it is easy to imagine a world in which space tourism becomes a hugely profitable industry.

The question then becomes: how much emphasis will be placed on advancing humanity when there is greater profit potential in offering short-term thrills with limited long-term benefits?

The next big adventure?

The spirit of adventure is clearly a key driver of discovery and its seems crucial to our on-going prosperity that humans don't lose this in-built curiosity.

And it is perhaps slightly hypocritical to criticise today's billionaires when the explorers of our more romanticised past were also mainly wealthy individuals (or were at least funded by them).

Ancient exploration was also funded by the wealthy dynasties of the era

However, there seems to be a danger of adventure for advancement and adventure for leisure becoming conflated to the detriment of both.

The increasingly popularity of adventure tourism shows that we crave a range of different experiences at various levels of risk.

But most of us would want to live in a world where these types of leisure activities were, broadly speaking, accessible for all and not the preserve of the rich and famous.

The instinct that drives someone's desire to leap off a cliff for pleasure can also help drive the discovery of a new medication, planet or species of animal.

It is the desire to push back the boundaries of what we know both of ourselves and the world around us.

This is a quality that should never be quashed, but we should also take extreme care to ensure it is utilised in the right way for the betterment of all.

Ready to start your IMI adventure? Contact us using the form below and let us guide you on your study journey!